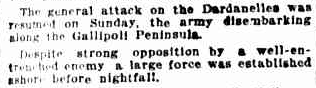

Today, Australians and New Zealanders commemorate Anzac Day, the anniversary of the landing of Allied forces at Gallipoli in 1915, and our national remembrance day for those who served in wars.

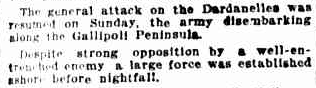

Report of Anzac landing at Gallipoli: Sydney Morning Herald, April 28 1915

The optimism of the early reports proved false as the Allied troops encountered strong resistance from the Ottoman army, and casualties were high. The campaign dragged on through eight months of stalemate, with heavy losses on both sides. According to Wikipedia, casualties in the Allied forces included 21,255 from the United Kingdom, an estimated 10,000 dead soldiers from France, 8,709 from Australia, 2,721 from New Zealand, and 1,358 from British India.Turkish deaths were around 60,000. Australia and New Zealand were both small nations at the time and the deaths of so many soldiers had a profound impact on national culture. The Allied troops were withdrawn at the end of 1915; Anzac Day was commemorated for the first time just one year after the ill-fated landing, in 1916.

Australian forces also served in Europe and the Middle East during World War 1, and many an Australian family has an ancestor or relative buried in a war cemetery, far from home. The 1914-1919 war hit hard, with almost every town losing some of its sons (and occasionally daughters) and seeing others come home, eventually, changed; but the reputation of our troops contributed to the forming of a strong national and patriotic spirit – the ‘Anzac spirit’ – in the still-young nation, which remains today, almost 100 years later.

When I travel through rural areas of Australia, I often pause at the War Memorials, many erected in 1919 or early in the 1920s; most of them with plaques, Honour Rolls or even extensions added in later years to honour those who served and died in later wars – World War 2, Korea, Borneo, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan.

I noticed such war memorials, too, when I travelled throughout Britain, and I know now how close my English grandfather came to being listed on one of them – he served in the British Navy on HMS Lion during the Battle of Jutland. But for the courage and sacrifice of Major Francis Harvey, it is likely that the ship and all aboard her would have been lost.

When I see these local war memorials, I remember that every name, every soldier, trooper, airman, sailor, or nurse, represents a life fundamentally changed and sometimes ended by war; a person with friends, family, spouse or lover who waited at home through long months or years of worry, dreading the knock on the door, the sight of the telegram boy, the ringing of a telephone.

As Bella observes in As Darkness Falls:

The Honour Roll to the side of the door caught a low shaft of early sunlight. Every Australian town had its war memorial – some a statue, some a rotunda, some a fountain or a clock tower. And some a memorial hall like Dungirri’s. For all the negligence and worn appearance of the rest of the town, someone had re-touched the gilt lettering of the Honour Roll recently, and cleaned away the cobwebs and dust.

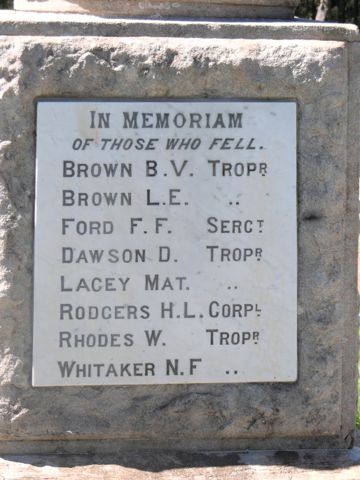

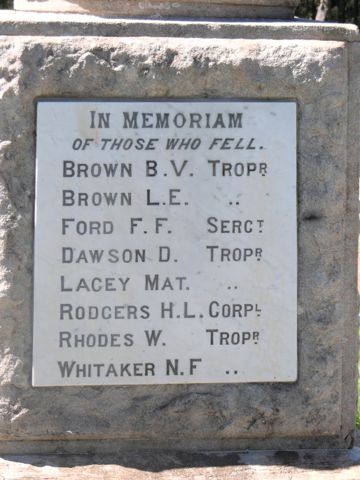

Newton Boyd War Memorial (on old Grafton Road, between Glen Innes and Grafton)

Newton Boyd War Memorial – Plaque listing young men from the district who died in the First World War, 1914-1919

Coolah Memorial School of Arts

Baradine Memorial Hall

Boorowa Memorial Clock Tower

Wellington War Memorial

From ‘A Gallant Gentleman’ in The Moods of Ginger Mick by CJ Dennis:

A month ago the world grew grey fer me;

A month ago the light went out fer Rose.

To ‘er they broke it gentle as might be;

But fer ‘is pal ‘twus one uv them swift blows

That stops the ‘eart-beat; fer to me it came

Jist, “Killed in Action”, an’ beneath, ‘is name.